The Perception Paradox

Innovation drives a lot of change within an organization and even across industries. However, the more change happens, the more resistance will emerge. Unavoidably, one key topic of innovation leadership remains the question of how to cope with resistance to change?

Robert Kegan stipulates that all resistance comes from the human mind and goes as far as conceptualizing a mental immune system that prevents some change while allowing for other changes. His work on “immunity to change” remains fundamental to every innovation leader when dealing with resistance to much-needed change. However, overcoming immunity to change imposes a non-trivial challenge primarily because of the intrinsic interrelation between the human mind, perception, and sensory processing. Before understanding that interrelationship, we start with how exactly immunity to change works.

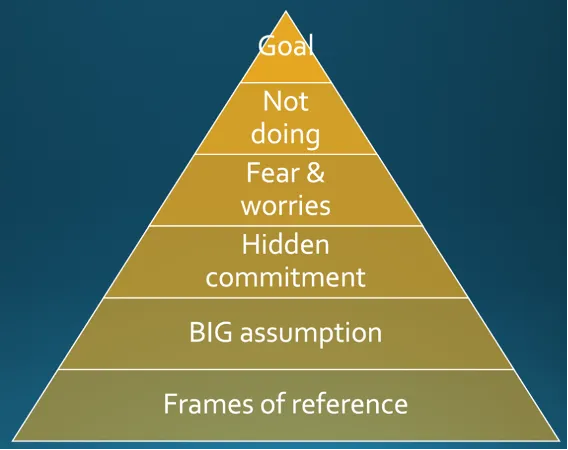

Robert Kegan conceptualizes immunity to change in four key segments:

- An improvement goal

- Fearless inventory

- Worry box & Hidden commitments

- Big assumption

Improvement goal

When aiming for something personally or professionally, you start with a goal. Fundamentally, a goal can be formulated as an outcome, i.e. becoming a sales director, or as a process i.e. increasing net sales. Notice in many areas of life, you have little influence over the actual outcome because of several external factors, but usually, you have a significant degree of leverage over how you structure your workflow and the overall process. Kegan, however, stipulates an improvement goal as a specific behavior that is about you and independent of anyone else. An outcome goal would be “I weigh 140 pounds” (implying a few pounds less than actual reality. In contrast, a process goal would be “I run a mile or more every morning.”

The behavior goal also serves as an easy-to-apply decision criterion for daily life. For example, when deciding what to eat for lunch, you can re-formulate the question: What food would support my healthy lifestyle? Taco Bell? Maybe not. Notice that neither the outcome nor the process goal supports daily decision-making. In summary, a good improvement goal:

- Is a behavior (never an outcome, process, or result)

- Is all about you (independent of anyone else)

- Is something you want to accomplish

- Is affirmative, positive, and active

- It is helpful to decide daily life situations

- You want a real improvement that is significant for you

Fearless inventory

Once you have formulated an improvement goal that is significant for you, you step back and observe what’s happening relative to advancing towards your improvement goal and take fearless inventory. Often, people do not work towards their goal (not doing) or, equally possibly, outright work against the stated improvement goal. To do so, you document your observations. Specifically, you look at what you are doing instead of working towards your improvement goals:

- The behavior you apply (eating junk food, for example)

- Non-behavior, things you should do but aren’t. (Eating healthy, for example)

- All your actions work against your improvement goal. (Socializing in the weekly KFC club, for example)

When documenting your observations, please ensure that you do not add any explanations or try any fixes. At this stage, it is too early to understand the exact reasons underlying your seemingly irrational behavior contrary to your stated improvement goal. Instead, dig deeper into the worries and fears underlying the document’s seemingly irrational behavior. And recognize that all worries and fears are never rational and, as such, cannot lead to any sensible behavior.

Worry box & Hidden commitments

At the third stage in the immunity to change assessment, you identify all worries that cause what you are doing instead of working towards your goal. In the healthy lifestyle example, you may worry if you leave the weekly KFC club, people may not like you anymore. Social belonging remains a fundamental human need and is an excellent source to prevent behavior changes regardless of how much needed these might be. In general, two sources of worries and fear avoid changes of behavior:

- Desired self-image: How people should perceive me

- Dreaded self-image: How people should not perceive me.

If your desired image is to be that funny, friendly person who is always at the center of the junk-food party, your immunity to change will fence off any perceived threat to that desired self-image. A healthy lifestyle conflicts with the desired self-image and therefore will be sabotaged to ensure it will not happen.

Likewise, suppose your dreaded self-image gravitates towards never being seen as incompetent. In that case, you will overcompensate by pretending competency at all costs, and naturally, your immunity to change will fence off any perceived threat of being exposed as incompetent.

Notice, in both cases, the emphasis is on the “perceived threat” to the self-image because rarely do these incidents correspond to reality. With that understanding equipped, it is relatively easy to formulate the worries and fears underlying the previously seemingly irrational behavior torpedoing your improvement goal. However, the identified main fear alone does not answer how to overcome your immunity to change.

Instead, we look at the resulting hidden commitment. A hidden commitment follows your fear, and it keeps the fear awake and alive. Fear and hidden commitment form a symbiotic relationship in that the hidden commitment ensures the fear does not come true. Still, the fear keeps the hidden commitment in place, while the hidden commitment keeps the fear. Fear and hidden commitment form a circular reference because one keeps the other. However, the hidden commitment only aims to protect the ego. It is not noble. It is the selfish self-protection of the fragile ego. Also, the hidden commitment explains all the things you are not doing or the fears you may have, which are brilliant ways of sabotaging your improvement goal. However, all worries and hidden commitments have one origin.

The Big assumption

All worries, fears, and hidden commitments root in one underlying big assumption. And it is called BIG assumption because it underlies all perception, thinking, and all actions. When you don’t advance towards your improvement goal, check your big assumption, and then you know why it all makes sense.

What is the origin of the big assumption, you may ask?

The big assumption forms over time through a series of experiences in which you make a similar conclusion. At some point, the human mind over-generalizes these conclusions into what becomes the big assumption underlying all your perceptions, thinking, and actions. In the previous healthy lifestyle example, you may have identified the following worry and hidden commitments:

Worry: “I worry if I stop eating junk food, I will lose my friends who are all into junk food.”

Hidden commitment: “I am committed to keeping socializing & eating junk foods, ensuring everyone keeps liking me.”

When looking at the actual behavior documented at the beginning, it makes sense, but at the same time raises the question of why you would do that. When looking for the perspective of the big assumption underlying all worries, fears, and hidden commitments, an uncomfortable truth will emerge.

Big assumption: “I assume, if I am too different, nobody likes me anymore” (therefore, I cannot adopt a healthy lifestyle …)

At this point, observing the big assumption in action is vital to verify it is real. If you can’t observe it, you may think again about what the big assumption will most likely be. And then again, this will be an uncomfortable hard truth. Still, when you find the big assumption, it explains the hidden commitment, rationalizes worries and fears, and justifies all behavior contrary to your improvement goal.

Furthermore, your big assumption selects and colors all of your perceptions. If you can’t see a possible path towards living healthy, it is so because your big assumption filters out those paths for you, so you can’t see that path in front of you regardless of actual reality. The obvious question is, how do you overcome the big assumption?

To answer that, we have to understand the perception paradox first.

Perception paradox

Your big assumption filters and colors all of your perceptions; however, your perception forms your mental model; then, your mental model shapes your thoughts. Your thoughts make your plans and actions, and your actions determine the outcome.

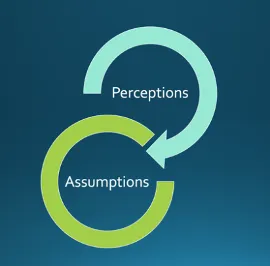

Any attempt to change the big assumption leads straight to the perception paradox as stipulated by Beau Lotto:

Acting differently requires thinking differently, but how can we think differently if our perceptions root in assumptions that interpret our perceptions? When perceptions create assumptions, and then assumptions interpret perceptions, then how can we possibly escape this vicious cycle?

There is little chance to change the big assumption on a rational-cognitive level other than making and perceiving experiences contrary to the identified big assumption. In the healthy lifestyle example, it is perfectly valid to join the weekly workout club and the daily healthy food club to realize one remains a valued member of society.

However, here is the catch, as long as the big assumption exists, the chances of actually doing these necessary steps are low. Often, we observe people failing to do the obvious in their lives for a very long time while simultaneously being blinded by those things we fail to do. And again, that’s the big assumption in action.

The key to breaking through the perception paradox lies in reversing the complete immunity to change process. To do so, we look into the anatomy of the human brain to discover the missing link required to invert immunity to change.

Neocortex & frame of reference

The neocortex, the most significant part of the brain responsible for perception, cognition, reasoning, and language, consists of a surprisingly uniform sub-structure regardless of the functional region. Specifically, medical experts have divided the neocortex into different areas based on the assigned functionality i.e. visual regions, touch regions, and so on.

One might think that auditory processing signals from the ear would be very different from processing visual signals from the eyes. However, that is not the case. Regarding neuro-biological structure, all functional regions of the neocortex consist of the same so-called cortical column sub-structures. A cortical column consists of approximately a hundred thousand neurons, about 2.5 mm tall and about 1 mm thick. Each cortical column is further sub-structured into three areas, object recognition, sensory features, and an intrinsic frame of reference. All cortical columns have the same structure, and have roughly the same number of neurons, and, in total, the sum of all cortical columns forms the neocortex.

The main difference between an auditory and a visual functional region is the sensory input to which the columns are connected. That means that tasks such as object recognition in perception are handled by the same structure regardless of the actual sensory input. As a result, all senses are processed simultaneously in many different cortical columns, which is why human beings can hear, see, and feel all simultaneously.

Because each sense is connected to many different columns, the perception remains stable while the surrounding environment may change at variable rates. Also, this allows the recognition of multiple objects in the same scene all at the same time. Because all senses are handled this way, it becomes apparent why, for example, circus artists can do a seemingly never-ending number of tasks simultaneously, such as juggling, riding a unicycle, and possibly playing an instrument. As odd as it seems, these artists lean intuitively on the most natural structure of the human brain.

One step further, each cortical column also comes with an intrinsic frame of reference. A frame of reference, similar to a coordinate grid, serves the critical function of relating objects to each other in terms of relative distance and similarity. Perception, though, relies on a constant frame of reference to ensure that, if you see the same thing again, you can recognize it as the same thing you have seen before. However, it is paramount to understand that frames of reference are learned from context, content, and interactions over time. This phenomenon of learned reference is biologically well established; for example, when a newborn opens its eyes for the first time, it sees the world upside down and left-right swapped. Only after some time does the brain set a visual frame of reference that corrects visual perceptions by de-mirroring the image before it feeds into the visual cortex for subsequent processing.

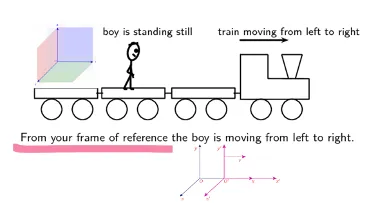

However, human beings are notoriously bad at understanding someone else’s perspective because we lack the implied frame of reference. To illustrate the exact problem, in the diagram below, the boy standing on the train perceives the world relative to its own frame of reference, which leads to the perception of standing still. An outside observer, looking from a different reference frame, sees the boy moving together with the train.

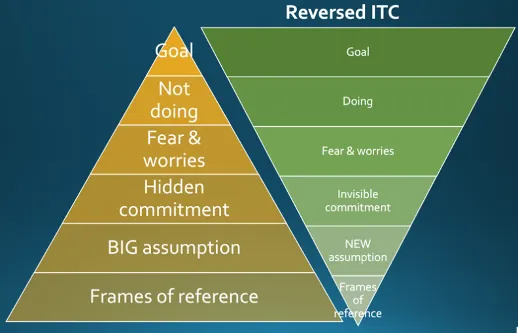

With the frame of reference being not only a neurobiological structure but also an essential factor underlying all perception, it is crucial to understand that the frame of reference holds all assumptions about the world in place. While we cannot reasonably change the big assumption identified through the immunity to change process, we can go one step further and identify the frame of reference holding that assumption in place. Not only the big assumption, but the frame of reference has all our assumptions. As shown in the pyramid diagram, underlying all assumptions lies the frame of reference forming the very foundation of the entire pyramid.

Solving the perception paradox

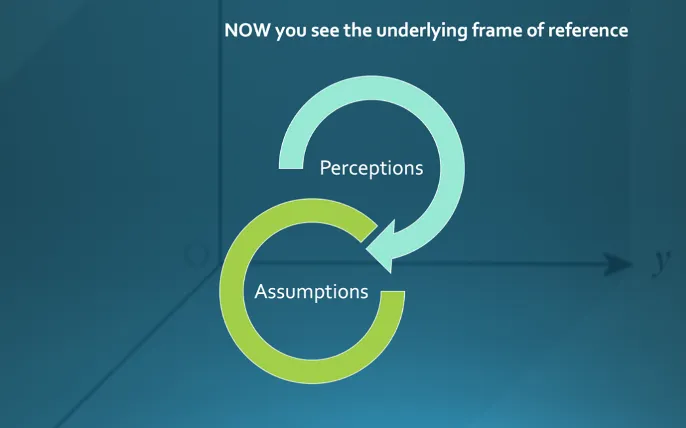

Solving the perception paradox means solving the frame of reference. Under your perception and assumption sit the frame of reference. Because of that, it is infeasible to remove a big assumption with reasonable effort.

However, the big assumption roots in unquestioned perception held by the frame of reference. The key here is “unquestioned” because the frame of reference sits below the perception level and, as such, is not subject to critical evaluation. Unlike your senses and common sense, you might not even be aware of if or how much your frame of reference might be miscalibrated.

Questioning the frame of reference requires a strange property of the human mind: Self-induced acceptance. If someone else tells you something, you may or may not accept it.

If you tell yourself the same thing, you accept it immediately. The human mind assumes by default that, whatever it comes up with, is at least not harmful and thus reasonable to accept by default. There is no good explanation for this property’s existence, but it is instrumental in tackling the perception paradox. The moment you ask a substantial question about your frame of reference, whatever your answer might be, the answer will be accepted.

Thus, the most practical way comes down to questioning your frame of reference, answering that question, and letting the brain do what it does best: Forming a new assumption.

From the moment a new assumption emerges, the ITC process inverts, and your mind drives you toward your improvement goal.

From practical experience, whenever people complete the process, a time of temporary disorientation follows mainly because of the imploded big assumption that once gave stability to all perception and reasoning, but even more so because of the de-framing, which results in the mind rebuilding a new frame of references rooted in reality.

The temporary disorientation lasts between ten days and four weeks but usually disappears without effort or action. Instead, the re-organization and re-formation of a new assumption conclude at some point. The moment people start thinking and acting upon a new assumption enables them to advance towards their stated improvement goal.

Furthermore, people report they do several other things they were not doing previously for personal reasons not explicitly stated. Often, participants report a deep sense of liberation after the temporary disorientation ends and new experiences contrary to previously held assumptions and beliefs start to unfold.

While we can solve the perception paradox with the proper understanding and intervention, the question of why immunity to change and the perception paradox even exists in the first place cannot be answered sufficiently.

Conclusion

After working for many years on answering the perplexing question of effectively overcoming the big assumption, I can only conclude that humankind needs to advance its understanding of the brain that contains and constrains the human mind. Specifically, we cannot understand perception sufficiently without a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanics encoded structurally in the cortical column of the neocortex.

Marvin F.L. Hansen,

History

- Written July 8, 2022

- Published Jan 7, 2023

- Moved to personal blog on March 16, 2024